Inleiding: Poelkapelle is Guynemer ... Anyone who passes by can not ignore it, even has to drive around. That village with that bird, the stork, the Guynemerdorp, our village. The statue, or is the tribe, as our parents talk about it, where we passed around every day since our first school passes. Master Baccarne even signed the monument in the drawing lesson. Not to mention the annual commemorations at the beginning of September, when on Saturday afternoon there was a French invasion every year.

Poelkapelle is Guynemer ... Anyone who passes by can not ignore it, even has to drive around. That village with that bird, the stork, the Guynemerdorp, our village. The statue, or is the tribe, as our parents talk about it, where we passed around every day since our first school passes. Master Baccarne even signed the monument in the drawing lesson. Not to mention the annual commemorations at the beginning of September, when on Saturday afternoon there was a French invasion every year.

What did that helicopter and those French Mirages make an impression on us and all those soldiers and flags. Indelible impressions leave that to a child of the village and then a lot later this tradition threatened to be endangered than such a child is entitled to continue that tradition, so that the village retains its grandeur and new generations the same fascination would increase.

How can you write something about Guynemer now, so much has been written about it and what is correct, exaggerated or even incorrect. I am barely interested in tapping into my dormant interest in the War for about 4 years. Who am I to write about a figure like Guynemer for a somewhat official website.

How do you approach him: only facts and figures, the person, or the whole cult around it. Very difficult. However, there is already a couple of works and an old little book on my table that best describes how I would like to do it, a mixture, but which also exudes the grandeur of yesteryear and indicates what Guynemer meant then . I myself can not make anything better to show how I felt it up to now. The booklet (but also other Guynemer attributes) was donated to the Franco-Belge du souvenir Guynemer committee by Guy Coussement with the explicit assignment to exhibit this material permanently to the Pool chaplers and tourists. This is therefore a first attempt to realize this. In the future we also try to display the other attributes and a real film from the old box for everyone who visits Poelkapelle. There are advanced discussions with café De Zwaan near the Guynemon monument to realize this together. This therefore fits in with the objectives of the umbrella association Poelcapelle 1917 Association which, in addition to the Guynemer Committee, also accommodates the tank group that tries to return the Guynemermonument to its British escort. But that is another story, which you will find more about elsewhere on this website

Georges Guynemer comes from a Flemish noble family whose roots can be found in the neighborhood of St. Omer. In the 11th century Georges moved his ancestors to Brittany and around 1800 they came to Paris. It was a patriotic family. Georges's grandfather, Auguste Guynemer, was vice-chairman of the "Société de protection des Alsaciens-Lorrains" (Bordeaux, page 29). As is known, the schoolchildren from 1871 to 1914 prayed "every morning for the return of the precious lost provinces."

Georges saw the light of day the day before Christmas 1894 as the youngest of three. He was attached to his two sisters Yvonne and Odette. The latter Georges would not survive for long. She died on 7 January 1919 of the Spanish flu. Georges spent his first years in the domain of his grandfather Auguste in Le Thuit, near Les Andelys on the Seine, where he was baptized. After an argument between his father Paul and his grandfather Auguste, they moved to his mother's castle, Julie Noémi Doynel de Saint-Quentin, in Garcelles, south of Caen. Finally, in 1903, the family settled in Compiègne, in a house that they had built on the edge of the forest. * The parental home in Compiègne was pillaged during WW II.

Georges was a good student, but he also had a fiery and stubborn character. He was sent out of school twice. When he, as an adolescent, answered an earflack of a teacher with an earpole, after throwing a frog to his head, his father took it for him. He felt that his son had behaved like a man. Before that time, this was unheard of.

His school education was interrupted more than once due to illness. At a young age, he contracted a bowel inflammation (enteritis), which would prevent him from going to the cavalry. Later he got the measles and scarlet fever. He was also susceptible to cold. In July 1917, just before he came to the front in Flanders, he was still attacked by an angina.

His fragile health, however, was not the reason why he was rejected by the medical service of the army. However, they are slim. He weighed only 48 kg for a length of 1.73 meters. That low weight was no disadvantage for a pilot. On the contrary. In a duel with his good friend René Dorme, who weighed 75 kg, Guynemer made it effortlessly. Dorme did not reach a height of more than 300 meters with a 50-hp unit, Guynemer increased to 500 meters without difficulty. But it is well known that the air force in 1914 was not yet autonomous and the recruitment of pilots was via the land army.

When Guynemer applied as a candidate pilot at the outbreak of the war in the aviation school of Pau, he was also rejected. However, the commander, Captain Bernard-Thierry, accepted him as a student mechanic. He circumvented the rules twice more by registering Guynemer as a student pilot and by learning how to fly himself, after he had crashed twice. In the beginning his fellow pilots called him "môme" (girl), but that would not last long.

Guynemer had acquired his passion for flying when he had seen a plane fly over at school. He had his passion for technology and for mechanics in particular earlier. At school he had once installed a telephone line with someone at the back of the classroom, using two food cans and a piece of string. That passion would stay with him.

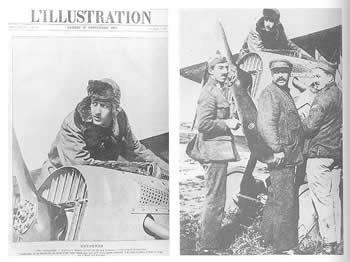

One of Guynemer's best-known photographs is the one on which, on the 10th of September 1917, the day before his death, he looks worriedly ahead of him on the hood of his Spad. He then landed at the Belgian airfield in De Moeren with a broken water pump. The Belgian aces Willy Coppens and Jan Olieslaghers had told him that their mechanics would solve the problem, but Guynemer wanted to see for himself what was wrong. He was as maniacally busy with his material as Merckx with his bike.

One of Guynemer's best-known photographs is the one on which, on the 10th of September 1917, the day before his death, he looks worriedly ahead of him on the hood of his Spad. He then landed at the Belgian airfield in De Moeren with a broken water pump. The Belgian aces Willy Coppens and Jan Olieslaghers had told him that their mechanics would solve the problem, but Guynemer wanted to see for himself what was wrong. He was as maniacally busy with his material as Merckx with his bike.

* Edited photo of Guynemer from L'Illustration of September 29, 1917 and the original. (Guynemer, un myth, une histoire, p.84)

Also known is the collaboration between Guynemer and Spad engineer Béchereau that resulted in the Spad XII, a device that was equipped with a 37mm-gun that shot through the propeller shaft. With such a Spad XII, Guynemer achieved four of his last five victories over Flanders

On July 27, 1917, Guynemer shot a German Albatross between Langemark and Roeselare. With one shot of his cannon and eight bullets from his machine gun he shot the machine to pieces. According to the German pilot Theo Osterkamp, Guynemer pulled down his aircraft that same day (an Albatros D III from MFJ 1). Osterkamp then had five victories and at the end of the war he already totaled 32. During the Second World War he was general at the Luftwaffe. He was present during the Guyemer commemoration of 1973 and he believed that Guynemer had spared him on 27 July 1917 when he crashed.

The day after, Guynemer took a DFW two-seater above Westrozebeke with two shots from his cannon (from 150 and 20 meters). That was his 50th homologated victory.

On August 12, 1917, Spa 3 left Bierne at St. Winoksbergen, where they had stayed since July 11, and settled in St.-Pol-sur-Mer, near Dunkirk. On 13 and 14 August they received the visit of the Belgian royal couple. It was then waiting for the Spad gun that needed to be repaired.

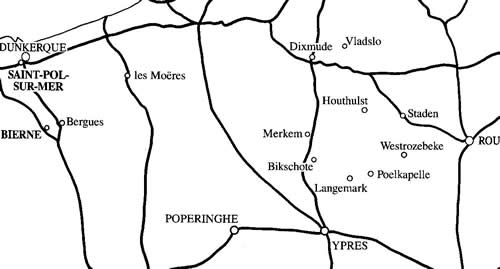

Places in French Flanders and West Flanders with the airports that Guynemer used and the places where he shot down his last victims. (Map: Klaeylé, 82)

On 17 August, Guynemer above Vlasdlo was able to beat an Albatros two-seater with the use of his machine gun alone. The pilot, Ernst Schwartz (° Cottbus, 9 August 1889) did not survive the fight. Five minutes later it was the turn of a DFW two-seater south of Diksmuide. Guynemer pulverized the device with one shot of his cannon. The observation plane crashed burning. The pilot, Johann Neuenhoff (° Wesel, April 9, 1894) died instantly.

The next day, Guynemer claimed another victory between Staden and Roeselare, but because the plane, a two-seater, disappeared over enemy territory, that claim was not recognized.

Guynemer's 53rd and last recognized victory, on August 20, 1917, he may have achieved with a Spad XIII. Above Poperinge he picked up a DFW two-seater at 9h05. The Spad XIII did not have a cannon, but two synchronized machine guns. Because his Spad cannon was still not recovered, Guynemer also flew out on September 11 with a Spad XIII.

On August 24, Guynemer went to Buc (near Paris) because he became impatient about the slowness with which the work on his Spad cannon shot. At Spad, engineer Béchereau had been succeeded by André Herbemont since May 1917. At that moment Guynemer was tired of war and confessed to pastor Aulagne: "C'est fatal. Je n'y échapperai pas!

On August 31, he flew back and forth to St.-Pol-sur-Mer for the visit of the Prince of Wales. That same day, his former commander Brocard proposed to definitively appoint him as captain. It is therefore not surprising that he still had his papers of lieutenant on 11 September.

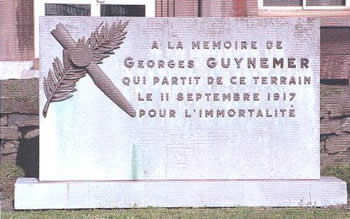

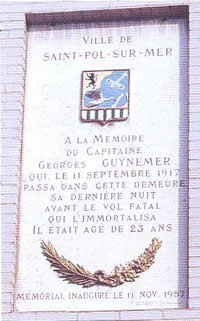

* Monument on the old airport of St.-Pol-sur-Mer near Dunkirk.

At the beginning of September, he spent several days in Buc and with his parents in Compiègne. On 5 September he was back in St.-Pol-sur-Mer and he received the order for Spa 3 because Captain Heurtaux was injured. That did not prevent him from flying a lot. Bordeaux mentions three flights that day, three battles without result from badly adjusted or blocked machine guns. Flooded for five and a half hours. The bad weather and many technical problems made him nervous and matted him off.

* Memorial stone on the house in St.-Pol-sur-Mer, where Guynemer spent his last night. That night the airport was bombed.

On 8 September, Guynemer flew out with Bozon-Verduraz. They got lost in the fog and returned only after noon, when they were already lost.

On Sunday, September 9, Guynemer attended Mass in St.-Pol and with La Tour he visited the wounded of their battle group in the hospital of Dunkirk.

On Monday, September 10, Guynemer flew again for five and a half hours and he had three times a breakdown with a different aircraft. First he had problems with the water pump of his Spad XIII (S 504) through which he served the countries in De Moeren. Back in St.-Pol he borrowed the device from the wounded Deullin (possibly Spad XIII S 501). In a confrontation with a group of German planes he was shot down - the eighth time in his career - and he returned with a car. With the third aircraft, a Spad VII (S 1764) of Lieutenant Lagashe, he had fuel loss, threatening to fire his aircraft.

That conscious Tuesday, September 11, Guynemer took off at 8h25 from the base at St.-Pol-sur-Mer. That was early, but Guynemer loved flying in the morning. "Then the enemy was less suspicious." But there was perhaps another reason why Guynemer was up early that day. His old commander, Captain Brocard, was coming and Guynemer feared that he was going to ban him from flying to save him. With 53 acknowledged victories he was unsurpassed at that moment and they could use it for other purposes.

* Monument for Guynemer in Dunkirk, with the bust of the monument of Malo-les-Bains, destroyed in 1941.

When the journalist Jacques Mortane ("mon historien initial") asked him what he thought of taking command of a hunting school, he responded as expected:

When the journalist Jacques Mortane ("mon historien initial") asked him what he thought of taking command of a hunting school, he responded as expected:

"- Do not speak to me about the stage area. I will not

respond to a proposal to take command of a school. First of all, I might be a bad teacher and I also think that the example is worth more than words. Look at Albert Ball, the English bait. They tried to send him to a school. After a few weeks he was already homesick for the front and he came back.

- Yes, but he died on 7 May 1917, when he had 44 victories on his list.

- I know. It is the fate of every fighter pilot. What does it matter? If I were to leave the front, people would soon say: "Guynemer? He has gone into hiding! "(" Embusqué ") One would forget my 50 victories and only see that the others are fighting and I am no longer there.

I think I will stay. I am ready. Often I hear claiming: "They will all go!"

Do you think that when I saw the poor Auger landing on our property to blow his last breath in my arms after his fight against three, this was not my first thought? I have been expecting this since my first flight. I only want to postpone the fatal day and avenge generously, anticipating my fall.

There are pilots who will never accept to go to the stage area, not even as a youth mentor. No, Dorme, who brought down one every day. He would never have deposited himself with a passive role. And by the way, teacher, everybody can be. It is often the least skilled pilots who teach best. The proof is that hunting is mainly taught by people who have never put it into practice.

As long as I stand, I will defend my title. It is not because I have received the highest honors or that I have nothing more to expect, that I will ask for my transfer to a quiet post. I have devised all sorts of tricks to be a soldier and then a pilot. I am in a situation that requires me to give the example. Leaving the front would be equivalent to desertion.

- There was nothing to say about that. There was no discussion with such a strong will and such noble patriotism. The army command tried to return the ace to his decision. It was in vain. The advice of friends and fellow pilots, who saw him gradually weakening under the load, did not work out either. "(Jacques Mortane, pp. 111-112.)

* Statue for Guynemer in Poelkapelle.

Guynemer could no longer step out of the hero role that he himself had chosen and that had also been forced upon him. He could only continue. "Just after dinner was not a quintessential" was one of the winged words he had received in his Christian upbringing and which he sought to live up to.

Was there such a place for a woman? To his companion François Battesti, the 22-year-old Guynemer said on August 31, 1917: "They do not know me well, because I only have one ambition. Listen carefully! If I survive this, I will be faithful and I will become a good family man. "Also the British topaz Mick Mannock, who was already 31, did not want to consider marriage until the war was over.